The conflict between Russia and Ukraine is raging not only in the physical realm but also on the cyber front, where governments, hacktivist groups, and individuals are trying to play their part. In this blog, we analyze some examples of the cyberattacks that have taken place as part of the current conflict and review their methods and impact.

Russian cyber warfare: Wiper malware

The military campaign was preceded by a sophisticated cyberattack launched by Russia against multiple Ukrainian organizations. It included highly destructive malware discovered by ESET researchers and named IsaacWiper and HermeticWizard, which are new variants of the wiper malware. The malware attack, alongside the military campaign, aimed to make an impact on the conflict.

The malware was installed on hundreds of machines in Ukraine and was followed by a wave of distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks. The new wipers can corrupt the data on a machine and make it inaccessible. In addition to the worm ability of spreading across a local network to infect more machines, they can also launch a ransomware attack and encrypt files on the compromised machine.

To our knowledge, this new wiper attack is targeting only Windows systems. According to internal Team Nautilus research, most cloud native environments (96%) are based on Linux. Thus, we assess that the risk to cloud native environments from this type of wiper malware is low. However, Russia’s cyber arsenal might include similar tools that are designed to attack Linux environments.

Hacktivists step in

As the Russia-Ukraine conflict unfolded, it attracted the attention of global threat actors such as the hacktivist group Anonymous. Anonymous regularly launches cyberattacks in support of its social and political ideals as well as against governments and their resources. In this case, Anonymous has declared cyberwar on Russia and called for hackers around the world to target Russian organizations and government.

Cloud native technologies used in cyber campaigns

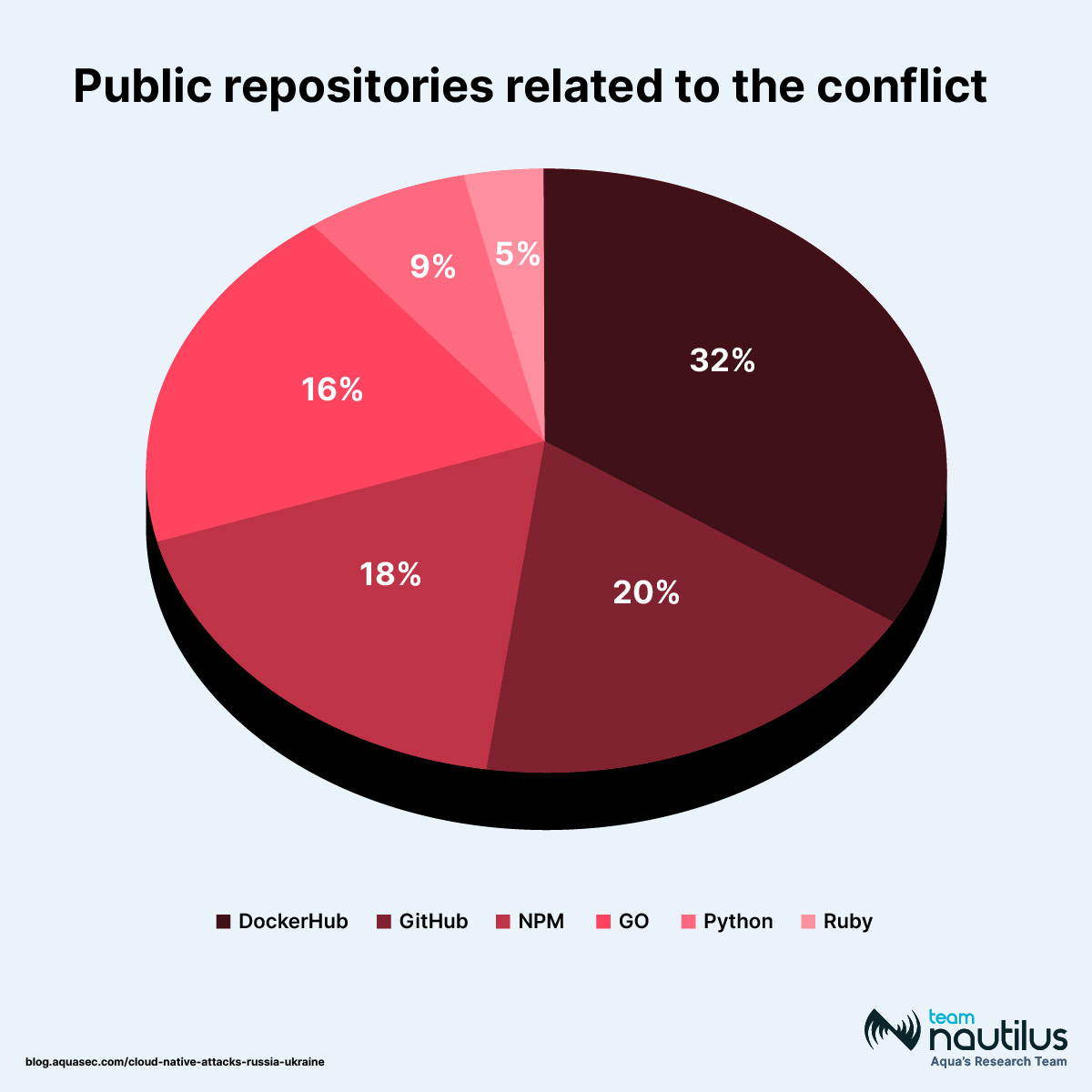

The attacks got our attention, and we at Team Nautilus tracked recent events to get an overview of the cyberattacks that have taken place. We gathered data from public repositories that contain code and tools aimed to target either side.

Among the repositories, we analyzed container images in Docker Hub as well as popular code libraries and software packages, including PyPI, NPM, and Ruby. We searched for specific names and text labels that called for an active action against either side.

As part of the Russia-Ukraine cyber attacks research, Team Nautilus studied public repositories with elements that call for an active action against either side

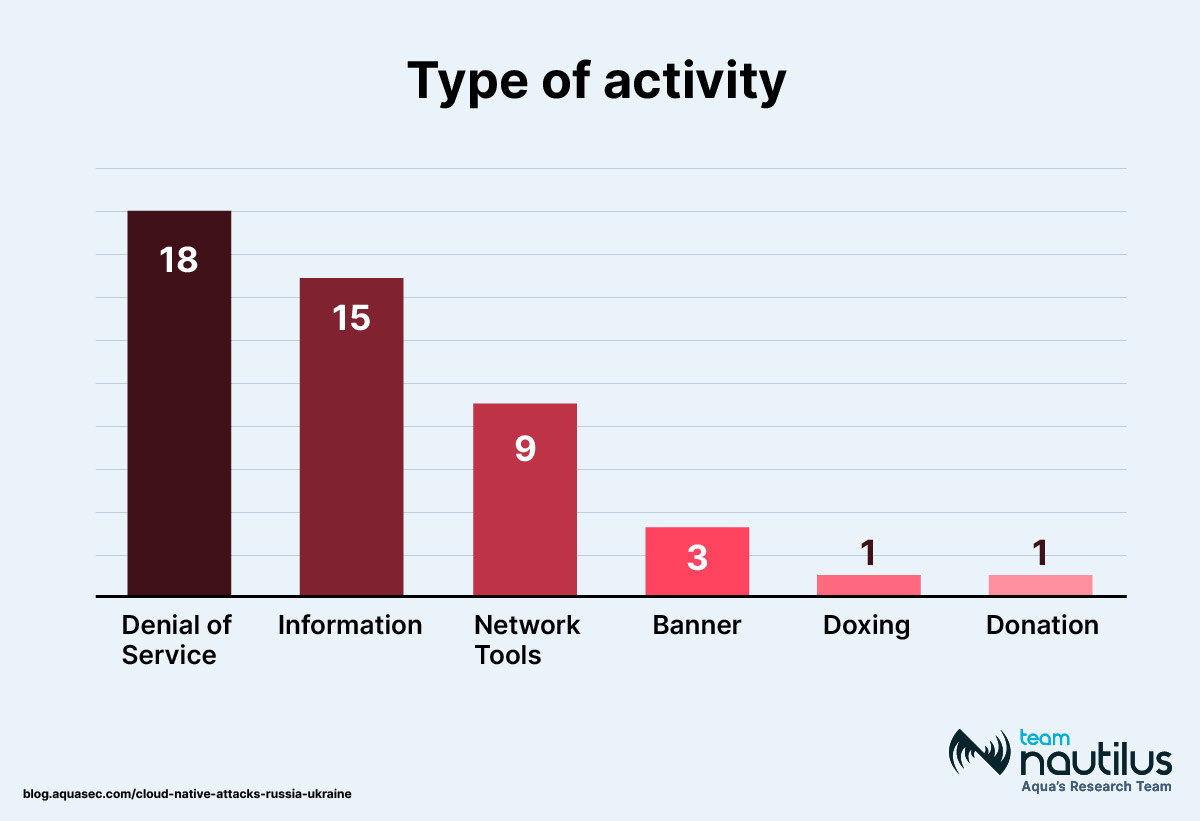

We investigated types of activities on these public sources. About 40% of the packages we observed were related to denial-of-service (DoS) activity aimed at disrupting the network traffic of online services. Other public repositories provided information to Ukrainian and Russian citizens or tools to block user networks from the conflict area. We also saw activity with a banner that can be added to a website in support of Ukraine. Moreover, there were sources that suggested doxing, which is publicly revealing personal information of high-ranking individuals. Finally, one resource collected donations to Ukrainian citizens.

Team Nautilus investigated types of activities on the public repositories that are related to the Russia-Ukraine conflict

Analysis of container images in Docker Hub

Next, we analyzed the container images abagayev/stop-russia:latest and erikmnkl/stoppropaganda:latest, which were uploaded to Docker Hub. The main reason for studying them was that together they gained more than 150K pulls.

These container images have published instructions and source code on GitHub, including a list of targets with Russian website addresses. Among other things, the guidelines explained how to initiate an attack and what tools to download, allowing non-professionals to launch an attack on their own.

As we see, the repositories have played a major role in the ongoing virtual conflict, making cloud native tools widely available to a less technical audience. This once again shows that today you don’t have to be a skilled hacker to take part in cyber war.

To analyze the container images above, we scanned them with Aqua’s Dynamic Threat Analysis (DTA) scanner. It executed the container images in a secure sandbox, which allowed us to gain more insights into these tools and their impact.

- The container image

abagayev/stop-russia:latestcontains a DoS attack tool that targets financial data and service providers in Russia. - The container image

erikmnkl/stoppropaganda:latestcontains a DDoS attack tool over TCP protocol through multiple connection requests. It’s used to initiate the attack and targets multiple service providers in Russia. - Both container images also included attack tools that initiate DNS flood carried out over the UDP protocol, sending a large number of DNS requests to UDP in port 53, and aimed against Russian banks.

Attacks in the wild

As part of our research efforts, we regularly deploy honeypots, i.e., misconfigured cloud native applications based on Docker and Kubernetes or other widely used applications such as databases. We analyzed the data recorded by our honeypots with a focus on attacks that launched DDoS attacks in the wild and collected only IP addresses that belonged to Russia and Ukraine.

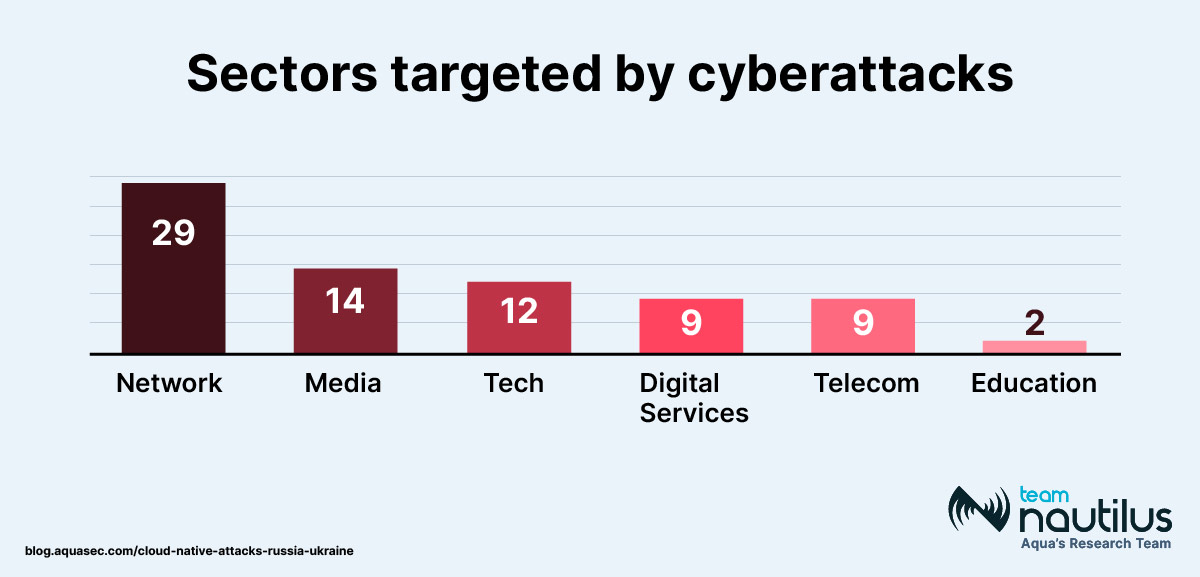

Based on the data accumulated in our honeypots, we found that 84% of the targets were affiliated with IP addresses in Russia and only 16% in Ukraine. Further sector segmentation of the organization metadata linked to the IP addresses shows that network and media organizations were the prime targets and were attacked most often.

Based on the data from Nautilus’ honeypots, the team also analyzed the targets of DDoS attacks in the Russia-Ukraine conflict

Conclusion

Our findings highlight the significant role that the cyber domain can play in a modern geopolitical conflict. As technology advances, experienced threat actors can create and distribute simple automated tools that allow less skilled individuals to participate in cyber war.

These advances also allow individuals and organized hacking groups to influence the conflict, using their knowledge and resources. We can see how emerging technologies are relevant in these efforts and can have an impact.

To learn how to protect yourself and your organization against these cyberattacks, check out the blog The Russia-Ukraine Cyber Attacks: A CISO’s Advice.

Indications of Compromise (IOCs)

| File | SHA1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| HermeticWiper | 912342f1c840a42f6b74132f8a7c4ffe7d40fb7761b25d11392172e587d8da3045812a66c33854510d8cc992f279ec45e8b8dfd05a700ff1f0437f299518e4ae0862ae871cf9fb634b50b07c66a2c379d9a3596af0463797df4ff25b7999184946e3bfa2 | ||

| HermeticWizard | 3c54c9a49a8ddca02189fe15fea52fe24f41a86f | ||

| HermeticRansom | f32d791ec9e6385a91b45942c230f52aff1626df | ||

| IsaacWiper | 736a4cfad1ed83a6a0b75b0474d5e01a3a36f950 |